|

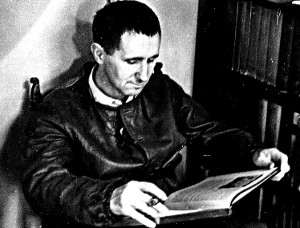

Bertolt

Brecht

(1898-1956)

German communist

playwright and poet. Began writing when he was young, he

become a communist in 1926, eight years after he completed

his first full-length play. For the next thirty years his

plays and poetry would be permeated with a critical,

revolutionary spirit, and a firm understanding and support

of class struggle. Forced into exile in 1933 by the rise of

the Nazis, Brecht continued to agitate, through his plays,

against the Nazi regime, and fascism in general. He remained

a principled communist till his death.

Plays:

Lux

in Tenebris (1919): 18 pages. A one act play about

prostitution. Brecht mocks and satirizes bourgeois hypocrisy

in regards to prostitution, i.e., the bourgeoisie are the

biggest public critics of prostitution, and use moralizing

and reactionary arguments against it, while at the same time

being the ones who run brothels, and who have always been

the main “clients” of prostitution.

The

Measures Taken (1930): 34 pages. Meant to be

educational, it is a lesson in the right and wrong way to

conduct agitation. It also has a very powerful message of

the type of sacrifice needed if you intend to seriously work

for a socialist revolution and the end of oppression.

Although it may be short, which perhaps is more of a

strength than anything else for this type of play, it is an

excellent example of using art for explicit political

agitation and education.

The Exception and the Rule (1930): 35 pages. An educational play demonstrating class differences and conflict, and showing that in no way can the working class and the bourgeoisie ever be reconciled: they are absolute enemies and the bourgeoisie will always win over the working class under capitalism since they are the ones who hold economic and political power. He

Said Yes, He Said No (1930): 15 pages. A short

didactic play against the unthinking adoption/following of

customs, and an argument for rational thought.

The

Mother (1931): 59 pages. A theatrical adaption of

Maxim Gorky's The Mother.

Saint

Joan of the Stockyards (1932): 101 pages. Brecht's

modern take on the story of Joan d'Arc: in this play she is

Joan Dark and lives in Chicago in the early 20th century,

and fights against social/economic oppression instead of

national oppression.

The Seven Deadly Sins of the Petty Bourgeois (1933): 17 pages. A very humorous short play which deals with the hypocrisy and idiocy of the bourgeois and makes the point that for the bourgeois, virtues that get in the way of accumulating wealth are unforgivable sins. Round

Heads and Pointed Heads (1934): 114 pages. Deals with

the absurdity of discrimination, whether based on race,

nationality, or religion, and how the ruling classes use

discrimination and bigotry to reinforce their oppressive

rule over all the laboring masses, no matter what their

origin.

The

Horatians and the Curiatians (1934): 24 pages. An

instructive play dealing with strategy and tactics, it is

Brecht's interpretation of the story of the Horatii and the

Curiatii, two groups of opposing male triplets: around 650

b.c., during a war between Rome and Alba Longa it was

decided that the outcome of the war would be decided by a

fight to the death between Rome's triplets (Horatii) and

Alba Longa's (Curiatii).

Senora

Carrar's Rifles (1937): 30 pages. This play takes

place during the Spanish Revolution, and presents

theatrically the conflict between advocates of non-violence

and advocates of real change and real struggle (i.e.

advocates of armed resistance). Brecht is very effective,

rhetorically and logically, in putting forward the argument

for armed struggle. The play also condemns indifference in

addition to the stifling influence of the clergy and it's

moralizing hypocrisy and backwardness.

Fear

and Misery of the Third Reich (1938): 91 pages. One of

Brecht's earliest anti-fascist plays, it is also one the

best and most well known. It consists of 24 small, unrelated

scenes which show the barbarity and inhumanity of fascism,

and explains the real meaning of fascism, and why it needs

to be fought always and everywhere it exists.

The

Trial of Lucullus (1939): 27 pages. Roman General

Lucullus is tried after his death by a lower class jury and

judge. Makes the point that “glorious, noble war” as it is

thought of by officers, means nothing but death and

disfigurement for the lower classes.

Mother

Courage and Her Children (1939): 84 pages. A cry

against the brutality and inhumanity of war, militarism,

warmongering, and a condemnation of those, like mother

'courage' who seek to profit from bloodbaths and massacres.

Dansen (1939): 15 pages and How Much is Your Iron? (1939): 15 pages. Both plays were written just before the formal outbreak of WWII, when Brecht was shortly in exile in Denmark and Sweden. They are both allegorical plays warning against the myth of neutrality and non-intervention in the face of Nazi militarism. Both are calls to action and resistance to fascism, and emphasize that fascists will sign as many treaties as they see fit, but they will look on them as pieces of paper to be discarded at will when it suits their interests. Life of Galileo (1939): 112 pages. A play that deals with Galileo's life, as is obvious, but more than that it is a plea for freedom of thought and intellectual creation and an attack on narrow-mindedness. The play also deals with the necessity of popularizing new ideas among the broad masses, and not writing solely for the intelligentsia. According to Isaac Deutscher, in the third volume of his biography of Trotsky: “He [Brecht] had been in some sympathy with Trotskyism and was shaken by the purges; but he could not bring himself to break with Stalinism. He surrendered to it with a load of doubt on his mind, as the capitulators in Russia had done; and he expressed his and their predicament in Galileo Galilei. It was through the prism of the Bolshevik experience that he saw Galileo going down on his knees before the Inquisition and doing this from an 'historical necessity,' because of the people's spiritual and political immaturity. The Galileo of his drama is Zinoviev, or Bukharin or Rakovsky dressed up in historical costume. He is haunted by the 'fruitless' martyrdom of Giordano Bruno; that terrible example causes him to surrender to the Inquisition, just as Trotsky's fate caused so many communists to surrender to Stalin. And Brecht's famous duologue: 'Happy in the country that produces such a hero' and 'Unhappy in the people that needs such a hero' epitomizes clearly enough the problem of Trotsky and Stalinist Russia rather than Galileo's quandary in Renaissance Italy.” Mr Puntilla and His Man Matti (1940): 96 pages. About relations between the working class and the bourgeois. A comedic play, Brecht uses the personality of Puntilla (he is one way when drunk, and completely different when sober) to mock the idiocies, arrogance, and petty discrimination of the bourgeois towards the lower classes. Brecht also makes clear that the bourgeois will always put themselves above others, and act superior, rude, and demeaning, and cannot be anything but enemies of the working class. The play also makes the point that normal people, and those who want to fight for them and stand by their side, should realize that no real friendship or positive relationship is ever going to develop between them and any normal upper bourgeois, and that they shouldn't want that either unless they want to be treated like servants. Brecht makes clear that hoping for good treatment from the bosses is an untenable position for the working masses, the right position should be working towards the complete elimination of bosses and opposing them at every move. The

Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui (1941): 121 pages. An

allegorical play that uses a gangster's (Arturo Ui's) rise

to power as an allegory for the rise to power of Hitler. It

is a very interesting play, in that it satirizes Hitler, a

mediocre if not completely incompetent person at everything

he put his hand to before his final rise to power, and yet

it explains his rise to power in a simple, very

understandable way. All of the characters in the play have

an equivalent to real-life people in Germany, thus Old

Dogsborough is von Hindenberg, Ernesto Romo is Ernest Rohm,

Emanuele Giri is Hermann Goring, Giuseppe Givola is Joseph

Goebbels, the Cauliflower Trust is the Junkers, Chicago is

Germany, and Cicero is Austria.

The

Good Person of Szechuan (1942): 105 pages. A

theatrical parable, it makes the point that morality,

honesty, virtue, etc, are determined mainly by the

prevailing economic system (i.e. the prevailing economic

system determines what is considered a "virtue"). The play

also points out that the integrity and righteousness of a

person is determined by their place in that system: thus if

they are an exploiter of human labor they are sure to be

unprincipled and repulsive generally because their economic

position dictates not only that they not care about

suffering and exploitation, but that they cause it in the

interests of accumulating wealth. On the other hand, the

poor and the exploited by their very position as

disadvantaged and oppressed have right on their sides and

are much less likely to be hypocritical, brutal, greedy,

etc.

The

Visions of Simone Machard (1942): 61 pages. An

anti-fascist play written after the occupation of France and

dealing with the need for resistance to the Nazi occupiers,

and against any collaboration with them whatsoever. It also

attacks the indifference and apathy with which the Nazi

invasion was initially greeted.

Schweyk in the Second World War (1943): 72 pages. A humorous adaption of Czech satirist Jaroslav Hašek's character The Good Soldier Švejk, the good-natured "idiot" who exposes hypocrisy and wins out over oppression in his own unique way. As opposed to Hašek's work, this play takes place during WWII (not WWI) and it's theme is resistance to fascism (not opposition to militarism), however both works criticize foreign control over Czechoslovakia. In some ways a humorous, literary analogue to the movie Hangmen Also Die! produced in the same year, with a screenplay written by Brecht. The Caucasian Chalk Circle (1944): 94 pages. Based on an old Chinese fable about who is more deserving of being a mother to a certain child, the one who has a purely formal claim to them in that they gave birth to them, or the person who deserves to be their mother and has loved and cared for them the way the first never had. A first approach to this subject by Brecht was a short story called “The Augsburg Chalk Circle” which you will find below. The

Antigone (1947): 50 pages. Brecht's adaption of

Sophocles' famous play Antigone.

The Days of the Commune (1949): 74 pages. A theatrical

depiction of the heroic Paris Commune, Brecht did a

fantastic job of capturing the idealism and enthusiasm of

the Paris Commune, as well as making clear the mistakes that

were made which helped led to its destruction.

The Tutor (1950): 55 pages. This play is about the subservience of education to the demands and interests of the upper classes, using as a metaphor a German tutor to the nobility during the 1700's. As the main character points out at the beginning of the play: just as previously tutors, teachers, and professors were subservient to the nobility, now they are subservient to the bourgeois, and thus teach what the bourgeois want them to. It also shows how some students' opposition to the mainstream, and rebellion against authority is easily overcome when they want a job as a teacher or professor: then they have no problem teaching what the ruling classes want them to and selling out. If a teacher does rebel or go against the mainstream, the upper classes try to cut them down to size and make them miserable so that they submit and teach their students the nonsense that other teachers teach their students. Thus this play shows, in a somewhat comedic manner, the bankruptcy of formal education under capitalism, and shows the necessity of education which actually focuses on enlightening and educating children, giving them a chance to develop their own interests and strengths without opposition. The Trial of Joan of Arc (1952): 41 pages. A beautiful play about one of the most well known resistance figures of Europe, Joan of Arc. She is often portrayed as insane, which is not surprising since anyone who fights against imperialism is subject to demonization and dehumanization by the imperial country and it's local collaborators. In reality, Joan of Arc was an intelligent, brave, strong peasant girl, who began fighting against British imperialism and occupation when she was only sixteen. In the play you can see her intellect, and the court dialog is kept very close to or the same as what she actually said. Of course Brecht does add his own interpretation, especially in the street scenes and the end where Joan refuses to sell out and betray her people. Joan d'Arc was burnt alive at the age of nineteen as a result of her heroic resistance to British imperialism and occupation. Turandot (1954): 67 pages. Brecht's final play, it explores the role of intellectuals in capitalist society, especially those who sell their intellect to the highest bidder and have no interests in opposing capitalism, but rather prefer to profit from it and live comfortable lives white-washing the truth for capitalists. A satire, it is somewhat of an adaption of Carlo Gozzi's comedic play of the same name. Short Stories: Anecdotes of Mr Keuner Caesar and his Legionary Socrates Wounded The Augsburg Chalk Circle The Experiment The Foolish Wife: An attack on the institution of marriage and how it is an economic institution with little or no concern for the rights of women, and how it builds itself, not on mutual feelings of love and respect between two partners, but rather on exploitation. At the same time the story celebrates true love between two people which doesn't cease in the face of tragedy, but if anything becomes stronger. The Heretic's Coat The Job: A stark portrayal of what it means to have to work to live in a time of recession and mass unemployment. Brecht also criticizes the view that women can only perform so called "womens work" or "feminine work," and makes the accurate point that anyone, man or woman can do any type of work, and act in any type of manner. The only thing that prevents this is the rampant sexism in society, and the societal conditioning of people into their "right" or "correct" roles, defined solely by their "gender," and not by the special abilities or interests that they may have. This story also shows what a job means to a worker who has been unemployed for a long period of time, and the lengths to which they are willing to go to obtain one. The Soldier of La Ciotat: About the absurdity of war, and how the producers of all things, the workers and the peasants, are the ones to suffer from it and the ones expended by the oppressor classes during it. The Unseemly Old Lady: Based on Brecht's own grandmother, it is a comedic attack on bourgeois notions of "propriety" and the way they want the elderly to act. Two Sons Poems: Collected Poems: 598 pages. The collected poems of Brecht, organized by time period in which he wrote them, extends from 1913, when he was 15 years old, until his death in 1956. Questions From a Worker Who Reads |