|

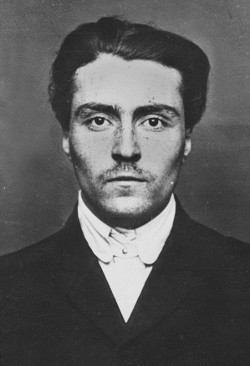

Victor

Serge

(1890-1947)

Russian communist writer and novelist, he was born in Brussels to two anti-czarists in exile. He grew up in poverty, never attending school due to his father's disdain of education under capitalism. Taught by his father, he also educated himself by reading widely. He joined the Belgian Socialist Party in his teens, however he found it too reformist and quickly moved towards anarchism. Shortly before he was expelled from Belgium in 1909 (for political reasons) he started writing for various anarchist publications. After moving to Paris he learned the printing trade, which he worked in at various times throughout his later life. Immersing himself in the lively anarchist community in Paris at the time, Serge soon became critical of the reckless "bandit" anarchism of many at the time, as well as their obsession with vegetarianism and other dietary limitations. In 1912 he was arrested and sentenced to five years imprisonment for his "involvement" with the anarchist "Bonnot gang." Innocent of involvement with the Bonnot gang, he refused on principle to condemn them although he didn't agree with their tactics. Upon his release from prison in 1917, he departed for neutral Spain and was briefly involved in the syndicalist movement there. He viewed the syndicalist anarchism as an improvement over the individualist anarchism he had known in Paris, but nevertheless was pained to see how naive and unrealistic many of the Spanish syndicalists were at the time. After the February revolution in Russia, Serge headed back to Paris with the hope of traveling to Russia. Shortly after arriving he was detained and imprisoned for more than a year in a concentration camp with other foreigners and deserters. Surviving as best he could in the atrocious conditions of the camp, he made use of his time engaging in political discussions and studying Marxism with the other Russians present in the camp. In October 1918 a deal was reached between the Bolsheviks and the French government, and the Russian revolutionaries in the camp were allowed to travel to Russia. Arriving in the Soviet Union in January 1919, he soon became a committed Marxist, which he remained till his death. Deciding to remain in Petrograd, the "revolutionary capital," he first took on several odd jobs before becoming the administrator of the Executive Committee of the Third International in March 1919. Joining the communist party in May 1919, he also participated in the popular defense of Petrograd from white general Yudenich in October 1919. Serge participated in the first three congresses of the Communist International. In late 1921, he assumed a Comintern position in Berlin, continuing in Vienna from November 1923, from where he joined the Left Opposition (of the Russian Communist Party). He returned to the Soviet Union in 1925 to fight side by side with his comrades in the Left Opposition. Expelled from the party in 1928, he started focusing on his writing. Serge was arrested in March 1928, then released after two months. Spending the next few years in a precarious existence due to opposition to Stalin, with hardship taking a heavy toll on his family, his wife even losing her sanity, he focused his energy on writing and translating when he wasn't searching for food for his family or medicine for his wife. Arrested again in March 1933, he spent three months in solitary confinement in Lubyanka prison. Subsequently he was exiled to Orenberg (in present-day Kazakhstan), where he stayed until 1936 when, due to protests from writers and intellectuals abroad, he was allowed to leave the Soviet Union. Staying the next four years in Belgium and France, Serge was accompanied by his children and his wife, with many of his remaining relatives to later die in Stalin's prisons. Continuing his writing abroad, he corresponded with Trotsky for a time, and joined the Spanish left-oppositionist Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (POUM). Fleeing the German invasion, Serge managed to escape to exile in Mexico, where he stayed, writing and corresponding, until his death. An independent Marxist whose payed a high price for his principled resistance to Stalinism, Serge was to the left of most of the Bolsheviks and Trotskyists. He was also a strong critic of the unnecessary repression of the Kronstadt revolt (on which he had a heated correspondence with Trotsky), as well as the lack of inner-party democracy which began very soon after the October revolution with campaigns against "factionalism" which started in 1920 against the Workers Opposition. Ignored and called an anarchist by Stalinists, he received the same treatment from Trotskyists since he was not adverse to pointing out the roots of Stalinism which existed and were nourished during Lenin/Trotsky's time. A deep thinker who lived the events he details, there is much to learn from his writings. Memoirs

of a Revolutionary: 396 pages. Insightful memoirs that

detail Serge's life very well, and ends in 1941. Written in

Mexico in 1942 and 1943 after his escape from Vichy France.

Well-written and honest as was Serge's style, it paints a

realistic picture of western Europe and it's working class

movements before WWI, as well as of Revolutionary Russia and the

many mistakes and betrayals that took place. Serge was an

open-minded Marxist, who for this reason was particularly suited

to recounting the heroism and shortfalls of both the pre-war

anarchist and socialist movements, as well as the Russian

Revolution from Lenin's time on.

What Every Radical Should Know (1926): 131 pages. Written while Serge was still in the Soviet Union and had access to the very recently discovered archives of the czarist secret police. Written to help revolutionaries abroad deal with reactionary repression, it details the workings of the Okhrana (czarist secret police): its handling and use of informers, its records and quasi-academic approach to compiling extensive information about revolutionary organizations, etc. It also delves into the issue of revolutionary repression, and other tactical and political issues that face a revolutionary movement. Although this book was written in the 1920's and technology has changed drastically, the majority of the book remains relevant to this day, and the general caution and methods involved in working underground are still relevant. Novels Birth of Our Power (1931): 221 pages. A largely autobiographical novel, it starts with Serge's time in neutral Spain during WWII, and with his subsequent involvement with the Spanish syndicalist movement in the tense time leading up to the attempted syndicalist uprising in Barcelona in 1917. The story then moves, as did the author, to Paris where Serge went to try to find a way to travel to revolutionary Russia. Subsequently imprisoned in a French concentration camp, the novel talks of the various interesting characters who were detained there, as well as the poor conditions in which they lived. Then, released from the camp, Serge went to the newly founded Soviet Union, and the novel recounts many of the first impressions of the protagonist, and ends soon after he arrives in the Soviet Union. A novel filled with revolutionary enthusiasm, and faith that the working masses' power will sweep the world, it does not hide the truth either, and shows the naivete of the Spanish syndicalists with compassion for their revolutionary enthusiasm, as well as the hardships in Russia after the revolution. Midnight in the Century (1939): 199 pages. A partly autobiographic novel based on Serge's time in forced exile in the remote south Russian city of Orenberg (pop. 120,000 in 1926). The novel focuses on several communists opposed to stalinism who are living in exile in a remote city. A portrait of the brave communists who refused to bow down to an oppression dressed up in progressive clothes, and who opposed the rise of stalinism with firm commitment to the true liberation and freedom of the masses. Reaffirms the importance of resistance to oppression, always, even in the most difficult of times. The Case of Comrade Tulayev: 309 pages. A panoramic view of Soviet life in the 1930's and the brutal and widespread stalinist repression. The main story line of the novel focuses on the assassination of "Comrade Tulayev," an important leader in the party by a disgruntled communist, and the wave of repression which follows. This is based on the Great Purge and the pretext for it's start: Sergei Kirov, a high party leader, was assassinated in 1934. His assassination was ordered personally by Stalin, to create the conditions for a wave of mass repression. This was only known for sure much later, hence Serge's different theory in this novel. An important novel that shows up-close and in detail the effects and extent of the stalinist purges, written by someone who experienced and suffered from them first-hand. |